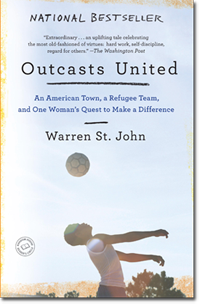

Excerpt

Introduction

ON A COOL SPRING AFTERNOON at a soccer field in northern Georgia, two teams of teenage boys were going through their pregame warm-ups when the heavens began to shake. The field had been quiet save the sounds of soccer balls thumping against forefeet and the rustling of the balls against the nylon nets that hung from the goals. But as the rumble grew louder, all motion stopped as boys from both teams looked quizzically skyward. Soon a cluster of darts appeared in the gap of sky between the pine trees on the horizon and the cottony clumps of cloud vapor overhead. It was a precision flying squadron of fighter jets, performing at an air show miles away in Atlanta. The aircraft banked in close formation in the direction of the field and came closer, so that the boys could now make out the markings on the wings and the white helmets of the pilots in the cockpits. Then with an earthshaking roar deep enough to rattle the change in your pocket, the jets split in different directions like an exploding firework, their contrails carving the sky into giant wedges.

On the field below, the two groups of boys watched the spectacle with craned necks, and from different perspectives. The players of the home team—a group of thirteen- and fourteen-year-old boys from the nearby Atlanta suburbs playing with the North Atlanta Soccer Association—gestured to the sky and wore expressions of awe.

The boys at the other end of the field were members of an all-refugee soccer team called the Fugees. Many had actually seen the machinery of war in action, and all had felt its awful consequences firsthand. There were Sudanese players on the team whose villages had been bombed by old Russian-made Antonov bombers flown by the Sudanese Air Force, and Liberians who’d lived through barrages of mortar fire that pierced the roofs of their neighbors’ homes, taking out whole families. As the jets flew by the field, several members of the Fugees flinched.

“YOU GUYS NEED to wake up!” a voice interrupted as the jets streaked into the distance. “Concentrate!”

The voice belonged to Luma Mufleh, the thirty-one-year-old founder and volunteer coach of the Fugees. Her players resumed their practice shots, but they now seemed distracted. Their shots flew hopelessly over the goal.

“If you shoot like that, you’re going to lose,” Coach Luma said.

She was speaking to a young Liberian forward named Christian Jackson. Most of the Fugees had experienced suffering of some kind or another, but Christian’s was rawer than most. A month before, he had lost three siblings and a young cousin in a fire at his family’s apartment in Clarkston, east of Atlanta. Christian escaped by jumping through an open window. The smallest of the dead children was found under a charred mattress, an odd detail to investigators. But the Reverend William B. J. K. Harris, a Liberian minister in Atlanta who reached out to the family after the fire, explained that during Liberia’s fourteen years of civil war, children were taught to take cover under their beds during the fighting, as a precaution against bullets and mortar shrapnel. For the typical American child, “under the bed” was the realm of ghosts and monsters. For a child from a war zone, it was supposed to be the safest place of all.