Author Q & A

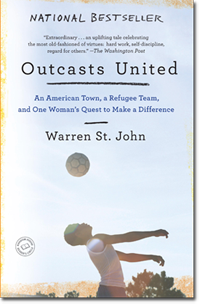

What is Outcasts United about?

In the most literal sense, it’s the story of a soccer team for young refugees, of the remarkable woman who founded that team, and of the town where these people came together. But more broadly I think of the book is about dealing with change -- large-scale social change -- as well as the problem of creating a sense of community in an atmosphere in which people, at least on the surface, don't seem to have a lot in common. I think the changes that occured in Clarkston are a hyperspeed version of the sorts of changes that are happening all around the world. So I went there to see what lessons there were to be learned.

Can you explain?

Well Clarkston, Georgia, where the Fugees are based, was once a simple southern town. And now between a third and a half of the town are foreign-born, and the high school has students from over fifty countries. Even the Fugees are comprised of kids from over a dozen countries, and the coach is from Jordan. And then of course there are people who’ve spent their entire lives in Clarkston. So the question then is, how do you make all this work? It seems like a fairly pressing question because this sort of change is happening all over the U.S. and Europe as well, though perhaps a bit more slowly than in Clarkston. That’s what attracted me to this story.

How did you hear about the Fugees?

I was in Atlanta giving a talk about my first book at a conference of educators, and a reader of the book invited me to join him and his wife for dinner. He worked in refugee resettlement, so over a hamburger, I suppose my reporter’s instinct kicked in and I started grilling him, asking, ‘Refugees from where? How did they get here? Where do they live and how do they build new lives here? Who helps them?’ That sort of thing. He very patiently answered my questions, and then casually mentioned that there was a soccer team of young refugees on the eastern side of town, and he encouraged me to check them out. So I called the coach, and went to a game. It was a surprisingly powerful experience. Luma was this mysterious, intense presence. The kids themselves were quiet and focused, and they played beautifully. And there was one player in particular who had survived an apartment fire a few months before that had killed a number of his family members. Luma was tough with him – he didn’t get a break at all. And without giving too much away, his response was remarkable. I came away from that afternoon truly moved, and I knew that day that I'd found my next book.

In the meantime, I learned more about Clarkston, and I realized that so much of the tension over refugee resettlement was just coming to a head. There had just been a case of police brutality against a Nigerian immigrant. That summer the mayor had banned soccer from the town park. So it wasn’t just a story a team – there was this momentous kind of reckoning going on in the community as well. And that’s what made it clear to me that I needed to get there quickly and to start reporting.

Did being from the South influence your interest in the story, or how you saw Clarkston in general?

Absolutely. I grew up in Birmingham, just two and a half hours from Atlanta. My mother is from Savannah, and I went to Atlanta countless times when I was younger, so I was familiar with the city. But mainly, I think I knew enough about the southern psyche, and life in a small town – my father was from a town in northern Alabama called Cullman, where I spent a lot of time as a kid – to know that the influx of a large number of refugees, including many from Africa and the Middle East, a decent number of them Muslim -- was going to produce some interesting fall-out.

You did a series of articles about Clarkston and the Fugees for The New York Times – did the book come out of that work?

It was actually the other way around – the book gave rise to the articles. I knew from the outset that this was a subject I wanted to immerse myself in, and the scope of it could easily support a book-length treatment, demanded it even. I talked to my editor at Random House, told him what I planned to do, and he was enthusiastic. So I was on my way. When I went to ask for a leave from the Times, my editors there asked what I was writing about, and when I told them, they asked if I’d write pieces along the way, during the process of reporting and writing the book. It seemed like a great way to test and formulate my thoughts about the material. But by then, I was already flying myself down to see games in Atlanta on weekends, and getting absorbed completely by the story. So I was working on a book a full six months before the first feature ran in the Times.

How were you received by the refugee families in Clarkston?

There is very understandable reticence among many of refugee families I met. Their experiences make it difficult for them to trust strangers, particularly anyone seen as part of an apparatus -- the government, the army, the media, even the relief bureacracy. Refugees have often faced a great deal of betrayal. That said, I had an introduction in most cases from Luma, someone the families knew and trusted, and that was invaluable. And among the refugees, there is also a natural curiosity about locals – they want to meet Americans and get to know them. They live in apartment complexes full of other refugees, many from other countries – people whose language they may not speak. So refugees in Clarkston don’t actually have many opportunities to just sit down and talk to an American. And when they do – they have lots of questions. They want things explained.

Can you give an example?

When I was reporting, I’d frequently show up – to soccer practice or games, to people’s apartments -- in a rental car. One afternoon one of players on the Fugees said, “You must be a very wealthy man.” I asked, “Why do you say that?” And he said, “Because you have so many cars – you’re always showing up in a new one.” So that became an occasion to explain the mundane but not entirely obvious practice of rental cars, and why one week you might have a mini-van, and the next week a PT Cruiser. Most refugees are coming from places where owning a car is exceptionally rare, so the notion that you could go essentially borrow one for a few days was almost unfathomable.

What do you think the hardest part of resettlement is?

Well – it’s all hard. Fleeing your home, usually amid violence. Getting separated from friends and family and having your life turned upside down. Life in a refugee camp – I visited several camps on a trip to Africa recently, and there was no electricity, no running water or sewage, and thousands of people living in mud huts or plastic tents. Then if you’re lucky enough to get accepted for resettlement, you’re given a loan for the one-way tickets to wherever you’re going, so you arrive not just with nothing, but several thousands of dollars in debt. You get three months of government help and then you’re on your own – even if you don’t speak the language.

That’s the obviously difficult stuff. Then there's the difficulty of fitting in in a new culture and place. And perhaps the most wrenching unforeseen hardship is the disconnect between the opportunity many refugees thought they’d experience in the United States and the reality of their lives once they get here. No matter how much of a beating the U.S.’s reputation has taken internationally over the last several years, most of the refugees I spoke to arrived here assuming the best about America – to an unrealistic degree. Many assumed this was a place where everyone gets a car and a house, and no one worried about food. And they get here and find out it’s not quite that simple. You have to get a job – commute, a concept utterly foreign to many cultures, where people work land very close to their homes. You have to worry about your credit and your rent, and pay bills.

And finally, the most difficult thing, probably, was when mothers like Beatrice Ziaty -- who had managed to get three of her sons out of fighting in Liberia to the U.S. – find themselves living in communities where gangs are active, where hearing gunshots at night isn't unusual and where they have to worry about their children’s safety all over again. So life here ends up being a lot more complicated than many expected. And that realization, weighed against the hopes that many refugees have when they arrive, can be extremely jarring.

The Fugees offer a refuge from that kind of activity. Tell me about Coach Luma.

Luma is a force of nature. She’s a doer. She offers an example of stability in an otherwise fairly chaotic environment. And perhaps more than anything, she does what she says she’s going to do. If Luma tells her players to show up at 8 a.m. to meet the team bus, she’s there by 7:55 a.m. Likewise when she says the bus is leaving at 8:10, the bus leaves at 8:10. So yes, by spending time with the Fugees – at practice, at games, at tutoring – that’s less time for boys to get into trouble or to get drawn in by the wrong crowd. But there’s also a powerful learning component to the entire program. The boys learn what it means to be consistent and to follow through, to take responsibility. And while some may find Luma’s rules rigid, they also come to appreciate their predictability.

Like a lot of people in the book, Luma is searching for a home in a way as well, isn’t she?

I think that gets back to what the book is really about. So many of the people I met in Clarkston – refugees, Luma, even the long-term residents, and especially a lot of the people who work in refugee resettlement – are looking for something: stability and safety, a sense of belonging to a larger community. And in a way that becomes the one thing that many people – even from very different backgrounds – have in common. The trick is opening enough of a conversation that strangers learn that about each other. And in Clarkston, there are these pockets where that conversation happens – among the Fugees players, at the International Bible Church, at Thriftown, the local grocery store. But it’s hard to realize that you and a neighbor may actually have the same interests if you don’t ever speak to each other.

And what about the distance between the Fugees and the teams they are playing? Do they ever have an opportunity to connect?

Yes and no. Fundamentally, when the Fugees take the field against a rival team, both teams want to win. It’s a competition, not an afternoon of group singing and camaraderie. That said, there are many members of the Fugees who have never been outside of Clarkston except to go to away games. Their parents don’t have cars. They take the bus to school each morning. So the simple act of traveling to a game – riding on the interstate past downtown Atlanta, or past some of those big beautiful houses in the suburbs with swimming pools and big green lawns – becomes an act of exploration into another world. And even the competitive banter and ribbing that goes on between kids – while not always entirely polite – is a form of communication and connecting.

There’s a scene early in the book in which the father of a rival player is watching his son select the proper cleats for his soccer shoes and he says something like, “I paid $200 for those shoes, so you better pick the right ones.” What did you learn from watching the economic disparity between the Fugees and their competitors?

I think the example of the Fugees might come as a relief to overspent soccer parents everywhere – you don’t have to have $200 cleats or matching team duffle bags with your jersey number embroidered on them to play the game well or to enjoy it. A passion for the game will trump having the best gear every time. I think that’s a shortcoming of the American approach to the game – we tend to emphasize gear and the consumer stuff, and to restrict play to a formal setting like practice and games, whereas most of the world plays the game all the time, more the way Americans play basketball. Watching the Fugees play definitely taught me about the value of cultivating that approach to the game and making room for it and encouraging it in a child’s life.

You’ve written a book about obsessed college football fans – Rammer Jammer Yellow Hammer. A book about young refugees couldn’t be much more different…

I think what the books have in common is that they’re both essentially about sociology, not sports. They’re about how people get along, how they organize themselves socially, how they – we – search for meaning in our lives and a sense of safety amid the unpredictability of the world. And while I don’t actually think of myself as a particularly obsessive sports fan or certainly not as a sports writer, sports does provide an interesting lens through which to view social phenomena. Sports makes people vocal – it provokes people to take sides and to temporarily suspend their inhibitions. People get out to see sports – they go to stadiums or to soccer complexes. They interact with strangers. The game distracts people just enough that they are willing to reveal things about their inner lives and thoughts that they might not reveal over a cup of coffee. Sports can act as a kind of truth serum.

In terms of specific subject matter, the books are very different. But for me part of the thrill of reporting a new story or a new book is delving into a world I don’t understand in the least and trying to learn my way out of it. That’s an exhilarating, humbling, edifying process, and it’s what I love most about being a journalist. So I fully expect my next book to be completely different from the first two.

In both books, you seem to avoid making judgments about the people you write about.

I generally go into most situations assuming that people are doing the best they can, and to challenge myself to try to understand the motivations behind actions that I disagree with or that strike me as wrong or wrongheaded. In the case of Clarkston, I think it’s important not to get caught up in the game of issuing simplistic moral judgments – saying this person is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ – but to acknowledge the complexity of a place and of the people there, and to acknowledge the incredible challenge resettlement has posed. So that’s what I’ve tried to do in my book. There are no simple answers in Clarkston, which is what makes it so interesting.